By Diane Baxter

Words from our performer:

“I feel at my most natural when playing many different pieces and love the freedom that comes with planning a recital programme,” she observes. “It’s so important, I think, to introduce audiences to wonderful music they may never have heard before as well as to works that they already know. So I will play …the known and the unknown….In this way I get to see things more clearly because of the contrasts and comparisons this gives.” From an interview with Valerie Barber

When Baldassare Galuppi (1706-1785) died, he was one of the most famous and highly paid composers in Europe. Unscrupulous publishers even put his name on some of Vivaldi’s work, which had fallen out of favor after the older composer’s death. Born on the lace-making island of Burano in the Venetian Lagoon, Galuppi was a very prolific musician. He composed operas, keyboard sonatas, sacred works and even theatre pieces. He served as music director at the Ospedale dei Mendicanti, whose mission was to treat lepers, beggars, and orphans. He later became choirmaster at San Marco’s and at the Ospedale degli Incurabili. Like the Mendicanti, this hospital was first built to treat incurable diseases, but later became an orphanage. Today the building houses the Venice Academy of Fine Arts. The iron grillwork behind which Galuppi’s choir sang is still present.

Today’s selected Sonata in C Major is lyrical and graceful, accessible and appealing. Galuppi’s style falls between the Baroque and Classical periods, so one hears some modified Baroque ornamentation, but with simpler textures. Transparent right hand melodies are accompanied by chords or Alberti basses. His formal structure represents a transition from the binary forms of Scarlatti to the fully developed sonata forms of Mozart.

It would appear at first glance that this Piano Sonata in G minor, Op.105, was written late in Felix Mendelssohn’s life (1809-1847). However, Mendelssohn only used numbers one through 72 during his lifetime, and the rest were added posthumously. Published twenty years after his death, this sonata was actually written by a 12-year-old child! Alex Ross, music journalist for The New Yorker, has written that Mendelssohn was the most amazing child prodigy in musical history. Goethe, the German poet, heard the child Mozart in 1763 and nearly sixty years later, the child Mendelssohn. He chose young Felix. According to Goethe, Mendelssohn bore “the same relation to the little Mozart that the perfect speech of a grown man does to the prattle of a child.” That’s a bit effusive, but also interesting! One of Mendelssohn’s most famous pieces, Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, was written when he was 17. The (in)famous wedding march, chosen by Queen Victoria for her daughter’s royal wedding, came along 16 years later.

The Piano Sonata in G Minor, Op. 105, is rather traditional in form, but its harmonic language shows the young composer’s precocity. The music has strength, wistfulness and an elfin delicacy that become characteristic of his future compositions. This sonata charms us throughout, especially as the playful third movement scampers off. Though it’s in G minor, it is sprightly and upbeat.

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) spent all but 19 years of his life in Russia/Soviet Union. Though he had graduated in 1909 from the St. Petersburg Conservatory, he avoided conscription into military service by returning as a post-graduate to study organ. He emigrated to the United States in 1918, citing revolutionary Russia’s disinterest in music. His time abroad (America, Vienna, Paris) was difficult and fraught with financial problems, but he met his future wife, Lina, in New York. Beginning in 1925, Prokofiev was courted by the Stalinist regime to return, with promises of performances, publications, and royalties. “They promised him no administrative duties and a nice apartment, a chauffeur, and a good lifestyle.” (Simon Morrison) Prokofiev traveled back and forth between Paris and Russia for a number of years, then returned permanently in 1936, accompanied by his wife and two sons. Prokofiev knew the grim situation in Russia but he was convinced by the official promises. Within a year, trouble started. One of his ballets for the Bolshoi was reviewed by the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians, who found it to be a “flat and vulgar anti-Soviet anecdote, a counter-revolutionary composition bordering on Fascism.” After the war, the Politburo took exception to Prokofiev’s music (along with others), calling it “muddled, nerve-racking” sounds that “turned music into cacophony.” Though Prokofiev avoided imprisonment during the Soviet regime, Lina was in a gulag for eight years for “treason to the motherland.” Spanish by birth, Russia was not her motherland. (For further reading, please see Simon Morrison’s The Love and Wars of Lina Prokofiev).

Prokofiev wrote this one-movement Piano Sonata No 3 before leaving Russia in 1918 and performed its premiere. He described this dynamic and energetic piece as “pretty, interesting, and practical.” Even though it is in one continuous movement, there are clearly three sections to the piece, basically a condensed sonata form. The driving, brilliant outer sections in A minor surround a lyrical and melodious middle section in C major. The performance requires strength, agility and endurance.

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) grew up with a great interest in mechanical things. He often visited factories with his brother, and claimed that it was “these machines, their clanking and roaring, and the Spanish folk songs sung by my mother in the evenings to rock me to sleep, which formed my first musical education.” He was very particular about how his music was performed, and even told his student, Henriette Faure, “I don’t ask for my music to be interpreted, only to be played.” In 1913 Ravel recorded the first two movements of the Sonatine on piano rolls (available on YouTube). Ravel released other rolls under his name that were actually performed by Robert Casadesus. That’s not as atrocious as it sounds. In their infancy, piano rolls were seen as a kind of toy, eventually showing up in every saloon. Given Ravel’s early fascination with machines, one can understand why he was drawn to these. The brilliant composer never recorded the demanding third movement, which was beyond his technical ability. His student, Perlemuter, once turned pages for Ravel in a concert of the work, but said, “I couldn’t tell where it might be tactful to do it.”

This Sonatine is in three short movements. The texture throughout is transparent with a preference for the upper half of the piano. Ravel includes a charming minuet in the middle, with a virtuosic third movement to bring the piece to a sparkling close.

Nikolai Kapustin (1936-2020) was born in the Ukraine and spent his early childhood in Kyrgyzstan. He graduated from the Moscow Conservatory in 1961, trained as a virtuoso classical performer. Kapustin didn’t like solo performing but he quickly became fascinated by composing in an amalgam of classical and jazz styles. He thought of himself as a classical composer working in jazz, but not as a “jazz musician.” He was particularly fond of Oscar Peterson, saying, “He’s No 1 for me.” Jazz had been suppressed during Stalin’s regime, perceived as another example of western excess. But Post-Stalin Kapustin was able to dodge scrutiny because he could always switch to classical composing if necessary. Unlike other Soviet composers, he was never threatened. He disliked improvising and believed his “improvisations” were better after they were written down, but they are astonishingly convincing. (Treat yourself to some video recordings of Kapustin playing with Oleg Lundstrem’s Big Band on YouTube. Kapustin sits with his back to the conductor!)

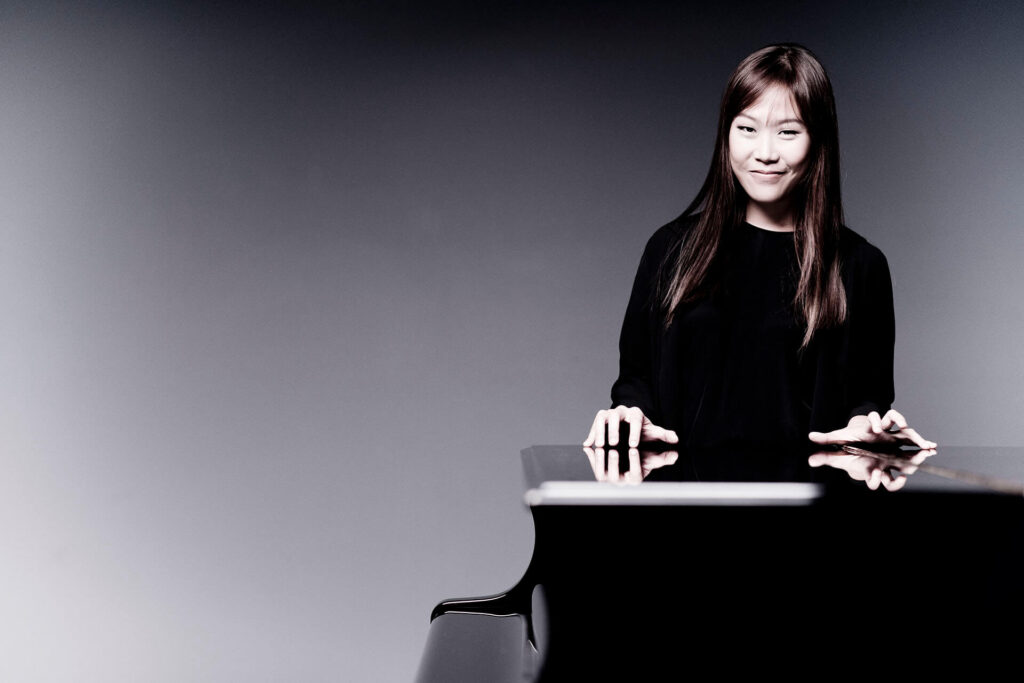

Today’s vivacious and buoyant sonata is in a traditional four movement form, but there is nothing else traditional about it. The music is wild, whimsical and capricious, though every note is written down. There is a rather contemplative ending to the first movement, which comes as a surprise, and the last movement is in a pattern of 8+7+8+5! However you choose to describe this sonata from 1989, we will be lucky if the Steinway doesn’t spontaneously combust afterwards. Hold on to your hats, buy Yeol-Eum a power bar, and call the fire brigade.

Author’s Note: Looking over this entire program, one can be thankful that the ticket price didn’t go up in direct proportion to the astonishing number of notes Yeol-Eum is playing today.

©Dianne Baxter